Matters of Classification

Many of you know that I’m currently pursuing my Master of Science in Library and Information Science degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s iSchool. I’m taking three classes this semester and I’ll have a handful of blog posts about various topics where library school and gaming overlap (hint: nearly everywhere). This particular post is brought to you by SP19IS502AO3, or Libraries, Information, and Society. One of my assignments due next week is titled “Matters of Classification/Classification matters” and the task is to “post a brief paragraph identifying a system of classification and considering its consequences.” We were told to pick ANY system of classification we wanted (even if we make it up as we go) and apply it to ANY collection, whether it was a spice drawer in a kitchen or an academic collection of manuscripts. I chose tabletop games and this is going to be more than a brief paragraph (I’ll have to somehow condense this for my classroom forum post!).

Note: this assignment was a brief exercise to show how many different ways there are to think about objects and data, how you can have 10 people organize the same set of things and come away with 10 different methods to do it, and how one object can have an unruly amount of terms with which to identify/label/categorize it. We aren’t getting into MARC records or any official sort of system here. This is an exercise in surface-level organization.

If you’re not familiar with the vast world of tabletop games, or even if you’ve started exploring it, it might surprise you to learn just how many different types of games are out there… Spend a few minutes poking around BoardGameGeek.com (a social board game database) and you’ll see a plethora of ways games are classified. Games can vary by theme, mechanisms, play time, recommended age, accessibility, designer, publisher, box size, player count, amount of space they take on the table, play rating… And all of these categories, and more, are the various ways by which people sort and organize their games on shelves. Whether you’ve got 30 games, 300 games, or 3000 games, chances are you’ve likely spent a little time thinking about how you were going to organize them on your shelves.

But… why does it matter?

Why does your method of classification or organization matter? Why do some folks agonize over how to sort their games onto shelves? Classification does a few things:

Organization can create a sense of order, which (hopefully) allows things to be found. If you organize your games alphabetically by title, you’ll know where to find Sagrada when you’re looking for it (as long as it was put back in the correct spot!).

Classification can tell others how we define things. If you organize your games by primary mechanism and put Sagrada in with drafting games, that begins to describe or define what others expect when they pull the game off of the shelf to play.

Classification can tell others how we value things. If you organize your games by your personal play rating and put higher rated games on top shelves and lower rated games on bottom shelves, finding Sagrada on your upper shelves tells people how much you liked the game.

Classification can tell others what we lack in a collection. If you organize games by theme and you don’t have a science fiction section, it might tell people that you may not care for science fiction games or perhaps you are not knowledgeable about science fiction games.

Classification can create an aesthetic. If you organize games by box color or box size, you might create shelves that look pleasing to the eye, but then you and your guests have to remember the color or size of every game box they search for… or stand there, staring blankly at a rainbow of game boxes until the one they want jumps out. And if you don’t organize strictly by size, you don’t maximize shelf space.

Establishing a set of classification rules can be incredibly helpful, except for when it’s not. Say you’ve got a friend over and you’ve asked them to pick a game – simple task, right? Say you organize your games by your personal rating and some of their favorite games are sitting on your lower shelves… Do they pick a game from your top shelf because they know you like it? Or pick one of their favorites even though it’s clearly not high on your list?

Or, say you organize by primary mechanic. Your friend historically dislikes deck builders, so they completely ignore that section of your shelves, not knowing there’s a game that has several other mechanics that they’d really enjoy… Their bias has ruled them out of a great game because you classified it as a deck builder… and, it’s not specifically any one person’s fault, it’s just a consequence of classifying things.

Or, say you ask your friend to get Sagrada off of your shelf. Your friend knows that you organize games by mechanism and heads over to the “drafting” section, but Sagrada is nowhere to be found. They look through the section several times, sure they must have missed it. Little do they know, you’ve put it in the “pattern building” section. Luckily they spot it as they give the entire collection a once over before heading back to the game table. Ideally classification saves time, but it’s not always the case.

To some, the situations above may seem far fetched. To some, the situations above may be very real. Some people don’t spend a lot of time on where their games go and they’ll put them on whatever surface has the space. Some folks may not have other people looking at their game shelves and feel that an organization system is not worth the time spent. But some folks spend a lot of time organizing their shelves for their own benefit and/or the benefit of others.

Apply the ideas above to a public space, such as a library… Libraries house MANY things… books, movies, music, games, technology, baking equipment, seeds, and so much more… and library patrons need to know how to find them and they want to find them quickly.

Classification coding exists in databases, catalogs, and even the physical space of the library itself. Signs point the way to children, teen, and adult sections of the library, as well as computer labs, maker spaces, and more. Every item that enters a library collection goes through several filters to land on the appropriate shelf. When an item is added to a collection database, it’s given a call number, description, keywords, subject terms, author and publisher tags, and more, so that the item will populate in relevant searches (but it isn’t as always easy as it might seem… see here, here, and here). Whoever does the coding has to assume what terms will be relevant to each item, or import an existing entry, and whoever searches for the item has to know the right terms to search with to find the appropriate items. And, just because you found the item in one library doesn’t mean you’ll find it under the same call number or section in another library system! Most libraries organize themselves based on what they think will work best for their own communities.

Anyway… board games! So, yeah, this assignment was to identify a classification system of our choosing, examine it, and consider the consequences of going with one method over another. I’ve done that above, with a few different systems used to classify board games, so on to what my fellow gamers said about their own collections.

Tabletop Community Responses

I know how my game shelves are organized, but I wanted to collect some information from the tabletop community to see how others organized their shelves, as well. Here are some of the responses I got (public responses are linked):

Jenn Bartlett:

Size, then publisher!

John Daigler:

We have two sets of shelves #1 – Games mom will play, #2 – Games only the boys will play. From there, the most played ones drift to the top, and stay there

Rich Harrington:

We have about 100 games on accessible shelves and at first I thought we don’t have a filing system, but a piling system. Big boxes on the bottom to small boxes on top with tiny boxes filling in gaps. But then I remembered, we have an unknown number of games in another closet for kids and then a shelf of 3-M type box games, so there is an organization. Our piling system does curtail buying more games sort of. If I were to reorganize, I would probably try to keep friends and family games (easy to teach, easy to play), horror games and then more complex games.

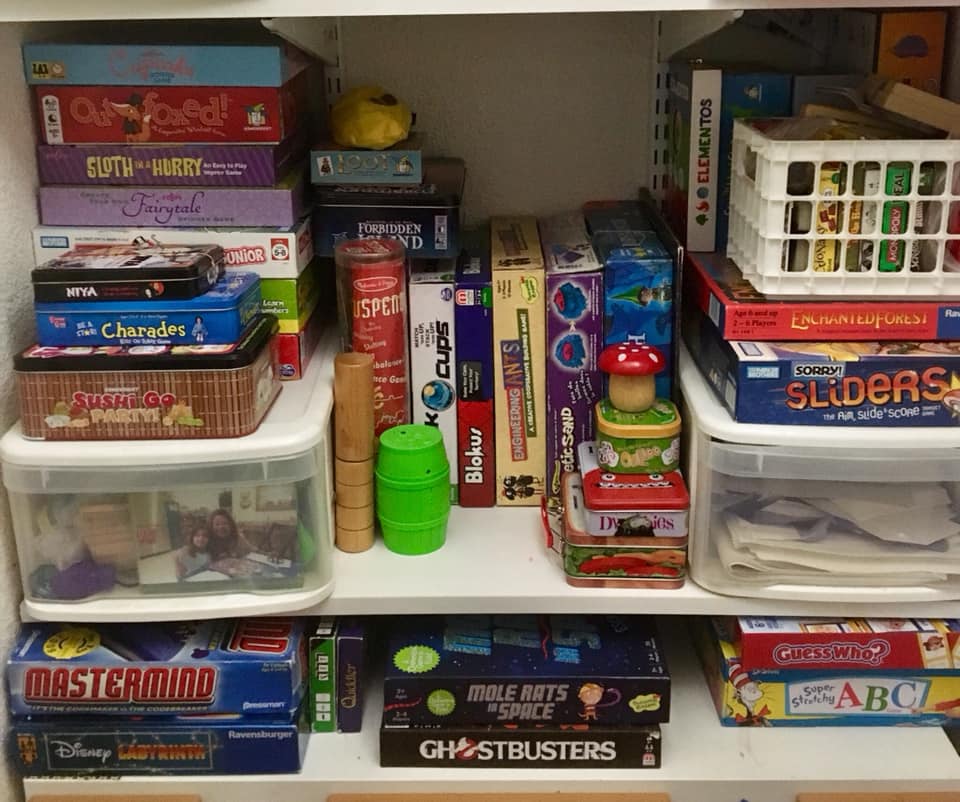

Hello! Fellow Librarian here! I didn’t start gaming until my child started at 3-4 yrs old. This is her game shelf. Just like everyone else, it’s whatever and however they fit on the designated shelf. My husband, the non-gamer in the fam, has instituted a rule that we have to get rid of one when we acquire a new one, (our house is *very* small). We have our ways of getting around that rule though 😜 … Not shown: the heavy rotation games we hide under the sofa. My games and/or games I’m saving for when she’s a bit older, that I hide in my closet

Annabelle Blackman

Denise Van Peursem:

I try to do theme, but it doesn’t always work since some kind of have combined themes.

Derek Schraner:

None of the above; by shape and/or size. With more games than space, just displaying them provides the most-played puzzle/game of all.

Ellie Taylor-Burr:

Our current system is “put everything on the new kallax we built when we moved in 6 months ago, in whatever way it fits”

For me, by size. I am constantly aggrieved by the fact that box sizes are so unjustifiably inconsistent. I use Billy bookcases and mainly I size the shelves to the box sizes. Every other organisational system goes out the window because I like visual consistency.

For my collection, it’s about 250ish games.

Meeple Like Us

AJ Le Brun:

Mainly by height, because we are a bit tight for space until the new shelf goes up, so we need flat surfaces to lay games on top of other games! But the 2 player games are all together so when people come over I can say “pick a game to play, but not those ones” 🙂 I have around 130 games.

Graham Best:

They are all chucked on the floor

Ben Healy:

[Primarily], different shelves for different box sizes. Games by the same designer go together assuming they’re the same size.

Monica Innis:

Mostly by size. Whatever fits.

I generally organize by type of game, but it’s gotten pretty loose as I’ve recently just been sticking games whereever they fit. But from left to right, my Kalax shelves have unplayed games, heavier strategy games, mid-weight strategy games, dice games, thematic games, light bigger box games and then game design stuff. On a bookcase I have small box games. A small Kallax has more unplayed games and games I need to play 1 more time. We have a rule that we need to play unplayed games twice each before deciding if it stays or goes, unless we really know for sure after 1 play.

Sarah Reed

Barbara Allen:

For the most part, by publisher or designer and then chronologically.

Caitlin Monesmith:

I organize based on what fits where- I have my board games and my DnD/tabletop stuff on the same shelving unit, so my stuff gets jammed in wherever it goes without falling.

Amy Lynn:

Since we have a smallish area, Jamie tends to Tetris things in where they fit best geometrically

Brian Deuser:

I tend to keep more frequently played games in the easiest to reach spot, then it’s all about fitting as much into what little space I have as possible

Colin Mancini:

As it stands it’s however they best fit, but once I get a legit shelf for them I’m considering going color coordinated, I’ve always thought bookshelves that are done that way look super cool

Designer is my primary sorting. For example, all my Felds are together, but aside from the Felds and Finn’s, everything is on a shelf based off size then. if boxes are a different size, it gets messy.

Michael Barth

Michael Barth shelfie #2

As you can see, when it comes to tabletop games, there can be as many classification systems as there are gamers. In some cases, even if the system is the same on the surface, gamers can have different definitions or parameters for their systems. And every system mentioned here (plus my own system in the next section) come with a variety of consequences, some of which we’ve outlined in the previous section.

My Game Shelves

My husband, Greg, and I have a large game collection (it’s part of the reason we’re doing a Depth Year). We run a gaming group that meets regularly, so we want our game shelves to have some form of order to them so our guests can find games on their own or with some guidance from us.

Organizing our collection was no small feat. Our games were in ever-changing piles on our basement floor while we figured out a system that works for us. We decided to organize the bulk of our collection with 4 main categories for board games:

- Games that handle either 1 or 2 players: all of these go in bins so they aren’t “on display” when our gaming group is over and looking for 3+ player games

- Designers/Publishers whose games we have in significant quantity – for us this is Feld, Rosenberg, Lacerda, Red Raven, and Stonemaier

- Campaign and legacy style games (Gloomhaven, 7th Continent, Sword & Sorcery, Folklore: The Affliction, etc.)

- Theme — everything that doesn’t fit into the categories above gets sorted by theme (dungeon delvers, witches/druids, fantasy, based on books/film, science fiction, cats, city building, horror, Lovecraftian, science, pirates, abstract, etc.)

Within each of the categories above, games are shelved in whatever way best maximizes shelf space in each section.

Vintage games, classic party games, and our stock of Extra Life giveaways are all on one set of shelves.

RPGs and interactive fiction books also have their own set of shelves.

Leave a comment

So, how do YOU organize your game shelves? Have you thought about why you use a particular method? Do you see any potential problem areas? Will you be updating your shelving organization?

Drop a line in the comments!

Nice! This seems to focus primarily on shelving-as-classification?

Have you also looked at some of the older classification scemes eg Bell and Murray? There’s also an interesting report from (IIRC) the Belgian game archive. They use a combination of dimensions including core mechanisms and theme – although there’s some overlap in the elements they propose.

Feel free to get in touch if you’re interested in some more references around this.

Yeah, this was a surface exercise. Some folks are looking at organizing spice drawers for this prompt. There were a lot of other factors that I didn’t get into here and only looked at it from a shelving/sorting perspective with no searchable database/catalog.

You’ll have to let me know when your thesis is available if you’re publishing it! I’ve used your other publications as sources for various assignments. It’s too bad we’re so far apart – I’d love to get together to play and chat about games!